In this short series of blogs, I will look at three of Cezanne’s paintings of Apples from around the turn of the century, 1900, just as he turned 60 years of age. Spending more and more time in Aix rather than Paris, he became a kind of rural myth, and began to attract young writers who heard of him through the admiration of artists living in Paris, and because he had been the school-mate and soul-friend of the now notorious anti-establishment critic, Zola. And - who’d have thought it – he was receiving his young admirers graciously! I hope you enjoy this, the second of three blogs….

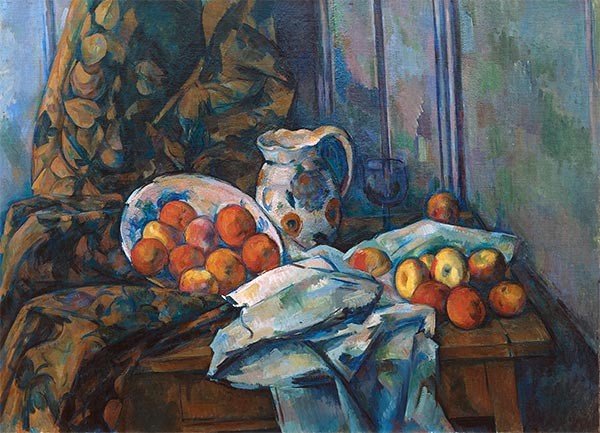

Still life with faience jug and fruit FWN 877 1900 73.1cm x 101 Winterthur

We left off our last blog encouraging our two authors - T.J. Clark in ‘If these apples should fall’ and Carol Armstrong in ‘Cezanne’s Gravity’ - just to enjoy the painting and forego the analysis!

And please, spare some time for beholding, and enjoying the painting: give yourself a break!

Ok, let’s analyze! Because, it is precisely the ‘space’ between our immediate perception of stuff and our pre-conceptions that we need to confront. We are more and more aware that we do not approach stuff with anything like a pure and balanced vision; our layers of interpretation, our understanding of the meaning of stuff, flow not simply from our own stories, but also from the collective understandings and values of the societies we inhabit. Hajo Düchting, in his book ‘Cezanne’, expresses it like this: ‘the conflict between flatness and depth becomes the spatial angst of modernity’. We are disorientated by the possibility that what we see, might not be the way it actually is.

Rainer Maria Rilke, as you might expect, expresses it somewhat more poetically in a letter to his wife and soul-friend, Clara : ‘Starting with the darkest hues, he (Cezanne) would add a layer that went somewhat further, and so forth, till by moving outward from shade to shade he arrived in due course at another, contrasting component in his picture, whereupon he would begin again, in similar manner, from a new centre….so that they instantly began to talk, as it were, constantly interrupting each other, continually at variance. And the old man put up with their disharmony.’ (Letters on Cezanne)

Let’s look at a couple of ‘centres’ that Rilke refers us to, as he tries to describe and understand how Cezanne constructs the space within the painting. Let’s focus on the plate and the jug: let’s see them as two adjacent spaces, and each of them is constituted by a space surrounding spaces. We understand the spaces within the plate-space to be apples; and the spaces within the jug-space to be flowers. Our mind tells us that the apples are real, but that the flowers are just a design. Our mind knows that jugs can stand up, having a base; but plates can’t stand up on their edge, so the plate must be held in its position by something – the fabric it sits on. So the fabric must be heavy, to hold up a plate full of apples; so it’s probably a heavy curtain. This conversation between the plate-space and the jug-space is how Rilke describes Cezanne’s method of constructing a painting.

The conversation continues not just in the delineation of spaces, but in the use of colours as well (indeed the delineation and the application of colour are very often one and the same). The colours of the plate-space and the jug-space are repeated and mirrored in each of the spaces within the spaces, as the jug-space leans into the plate-space and indeed holds it up where the curtain cannot accomplish this task. These tensions provide mutual support and interdependence for the plate-space and the jug-space. “They begin to talk, constantly interrupting each other, continually at variance. And the old man put up with their disharmony”.

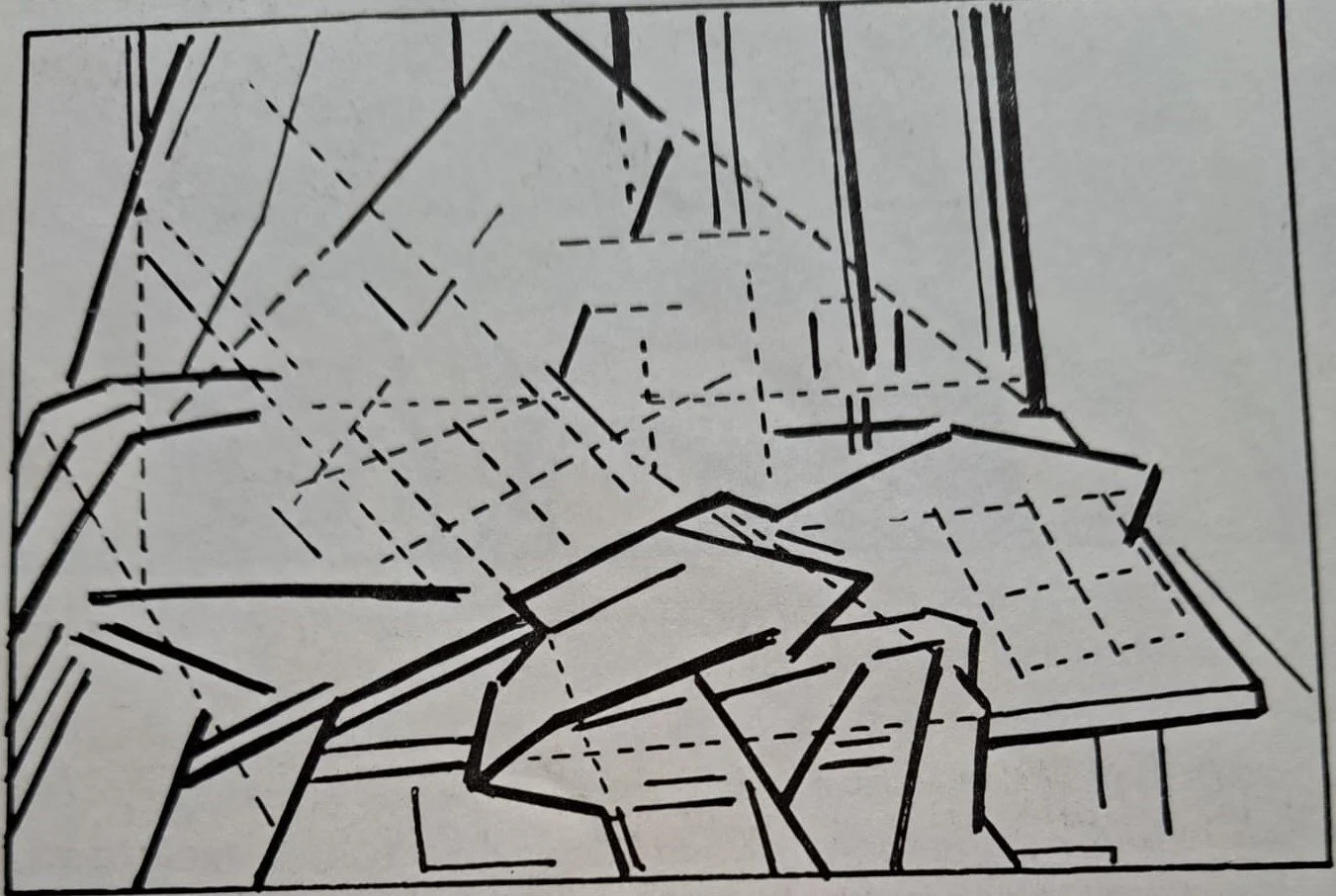

Now zoom out – and consider these, from Erle Loran: Cezanne’s compositions:

This analytical tool shows how the painting achieves its structural power; Cezanne’s masterpieces have that kind of ‘bumf’ to them – they’re somehow solid and earthed, like an ancient pyramid; they’re just there! Strong and confident enough to face you as equal; existing in their own space, in their own right! You approach them with respect, and even reverence!

We understand vertical and horizontal lines as static, while diagonal lines we recognize as moving and dynamic. There are no vertical or horizontal lines in this painting.

So, while it’s solid and earthed, it’s still moving and dynamic.

This analytical tool demonstrates the decorative and abstract elements of the painting. The dotted lines, now extended from the pyramid shape into a diamond shape, “are based almost entirely on subjective or carry-through lines”(Loran) – non-objective or abstract shapes. Within the diamond, Cezanne places as many decorative shapes of different sizes as he feels able, while maintaining a balance: circles, ellipses, triangles, rectangles. Three of the six apples at the bottom right form part of the abstract line of the diamond, while the lower three (with the help of the white table cloth) towards the edge of the table act as a counterbalance to the heavy curtain, pushing their corner of the table down, as the heavy curtain tends to topple the table over.

Now we can clearly see how Cezanne has gone about the promise he made “to make out of Impressionism something solid”. He has taken the beautiful things in humble places realized in the Impressionistic painting ‘Two apples on a table’, and made of them something solid, yet dynamic in the painting ‘Still life with faience Jug and Fruit’.

What’s fascinating is that Cezanne is painting these paintings around the same time, maybe side-by-side: he is describing the stages of his own development, in the language he knows best – oil paint on canvass.

I’ll examine Cezanne’s development and his awareness of his own development in the next and third blog.